Today David Koch, one of the 15 richest men in the world, died.

He and his brother founded a private company, Koch Industries, which is engaged in refining, chemical production, and other industries. Entrepreneurs are known for their active lobbying, violation of environmental laws and ambiguous political views.

The GRIN tech studied the history of one of the largest private companies in the United States, Koch Industries, and its shareholders – brothers Charles and David Koch (84% shares), who are known for their active lobbying, violation of environmental laws and ambiguous political views.

The U.S. giant Koch Industries, owned by the Kohov family, is one of the world’s largest private companies and is also the second-largest in the U.S. in terms of revenue. Its head is Charles Koch, and his brother David is the executive vice president.

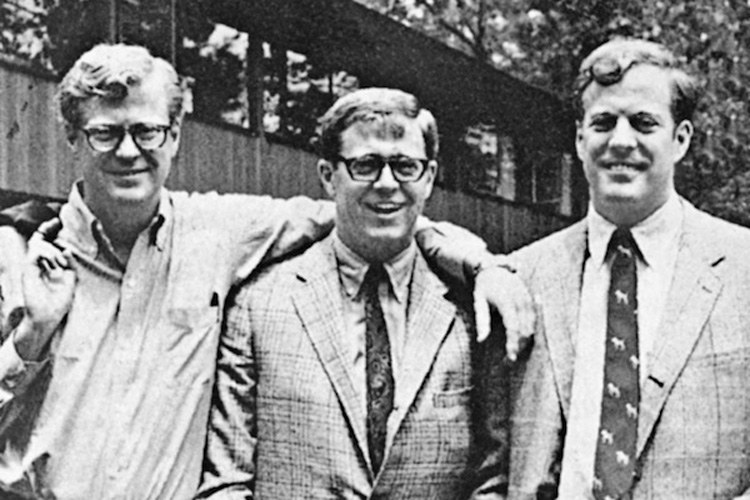

Koch Brothers Photo

The brothers are among the most influential lobbyists in the U.S., actively support the Republican Party and have long been opposed to Obama. In the past elections, Kochi unexpectedly did not support Donald Trump for many. They did not interfere with the latter but may well complicate the life of the newly elected U.S. president.

Outline

- Fred Koch and the creation of a family business

- Charles Koch is in charge of the company. The first successful deals

- The struggle between brothers for power over Koch Industries. Violation of environmental laws

- Koch Industries in the 2000s. Trade with Iran

- Features of conglomerate management. Political views and initiatives of the Koch brothers

Fred Koch and the creation of a family business

Koch Industries was founded by Frederick Koch. He was born in 1900 to a Dutch immigrant family. Koch received an excellent education and became a certified chemist and worked for several oil companies. In 1925 he joined Keith-Winkler Engineering. After one of its owners left the business, Fred took its place and the company was named Koch-Winkler Engineering. Soon Koch invented a new efficient way of refining oil into gasoline.

This would have ensured the company’s growth and increase in the number of customers, but there were already quite large players in the refining industry, and they were not in a hurry to share market share. Companies chose a simple way to destroy a small competitor – patent lawsuits. A total of 44 lawsuits were filed against Koch-Winkler Engineering.

Winkler and Koch did not give up and started to fight back, and although they managed to win 43 lawsuits, the 44th turned out to be a failure. In 1932, Koch-Winkler Engineering stopped working in the U.S., but not in other countries. Later, Koch learned that he had lost the suit because of a bribed judge.

Not being able to operate in the U.S., Koch and Winkler switched to other markets back in 1929. Soon, their attention was drawn by the Soviet Union – Koch built 15 refineries in the USSR within three years and earned $5 million.

Work in the Union went well, but communism provoked antipathy in Koch, which will be passed on to his sons. It is said that he even established rules for his sons – not to trust the Communists, not to borrow and not to sell the family business. In 1960 Koch even published the book “The Businessman Looking at Communism”, where he remembers the times in the USSR in a rather negative way.

In addition to the Soviet Union, Koch has successfully worked in many countries. One of the most famous oil refineries opened by Koch appeared in Nazi Germany at the personal request of Hitler. Some sources do not mention the participation of Winkler in the creation of refineries – researchers tend to believe that Fred Koch worked independently.

By the beginning of the 1940s, the entrepreneur had a relatively large fortune, but he was in no hurry to relax. Soon he and his new partners created the oil company Wood River Oil and Refining Company. In 1946, she acquired Rock Island Oil and changed the name to Rock Island Oil and Refining Company. Kocha worked steadily but did not become a national concern. Fred had four sons – Frederick, Charles, David and William (the last two were twins).

Koch Family in the 50s

The second son, Charles, showed the highest potential. Fred wanted to teach his children to work, so Charles had to work after school and also in the summer. Kohu benefited from such education and later became an active and hard-working man.

Charles studied at the University of Massachusetts, where he studied mechanical engineering and chemical engineering. During his studies, he became a member of the Beta Theta P brotherhood. After successfully completing his studies, Charles found a job with a consulting company.

However, his work in this field did not last long. In 1961, Fred Koch, who had previously suffered from heart problems, asked his son to return home and start a family business. Charles wasn’t an inventor like his father, but when he found himself at the head of the company, he decided he wanted to build something huge. Before handing over the business to his son, Fred Koch stressed that he could manage as he wanted, but he had no right to sell the company.

At that time, Rock Island Oil was unstable, and the refining business had a profit of $1.8 million, but the engineering business only compensated its costs, remaining unprofitable. It did not set any global plans and had a number of management features that did not allow to achieve global growth. Having headed his father’s business, Charles began by correcting the mistakes he had noticed.

One of Charles’ first actions was the expansion of the company’s pipelines not only in Rock Island but throughout the United States. The idea proved to be effective and profitable. At that time, however, Koch Sr. was still in business, and at first, Charles remained more of a student than an independent entrepreneur.

In 1967, Fred Koch died after a heart attack on a hunt. In his will, he indicated the heirs of all four sons, splitting the shares equally. This will eventually lead to a split between the brothers.

Charles Koch is in charge of the company. The first successful deals

Charles took over as head of the company and soon showed his entrepreneurial skills. One of his first instructions was to rename his father’s company Koch Industries. The next point was the purchase of the Pine Band refinery, one of the largest in the United States. At the time of purchase, Koch owned only 35% of the enterprise. In order to get the whole thing, it was necessary to carry out a series of manipulations.

Charles agreed with Jay Marshall, owner of 15% of the enterprise, to cooperate – and borrowed $25 million from him. Then Charles bought about 40% of the plant from Unocal for the money he received. Marshall’s loan had to be repaid to Koch Industries. The deal was seen as risky, but it turned out to be extremely profitable.

Charles had to convince his brothers for a long time to get into Marshall’s business. It was as if Fred Koch had taught his sons to keep the family company away from outsiders from childhood. Marshall turned out to be a good shareholder, and on several occasions even supported Charles.

In 1969 Koch Industries merged with Atlas Petroleum Limited Bahamas. The latter was then a major distributor of crude oil and other petroleum products with sales of $100 million. In 1970, David Koch joined the company and, like his brother, studied chemistry at Massachusetts University.

At the same time, Charles took on a new idea. The idea was to establish a tanker service. Despite his efforts, the idea did not end successfully because of the oil embargo imposed by OPEC. Koch had to sell out his tanker fleet, retaining only one vessel. David Koch recalled that Charles was under constant stress at the time and was forced to fly to London to try to restructure his debts.

However, thanks to the rise in oil prices Koch Industries has increased its revenue by 14 times in the 70s. In 1974, the company controlled more than 10,000 miles of pipeline, hundreds of tanks, subsea terminals, and barges. All this together allowed the company to ship more than 80,000 barrels of oil per day.

How Koch achieved this result is not known for certain, and given the fact that Koch Industries remains a private company, many aspects of its operations are kept secret.

In the 1970s, the federal government launched a lottery to split up exploration plots to ensure equality between small and large players in obtaining them. The winners had the chance to lease the plots for 10 years at a price of $1 per acre.

Koch Brothers

Koch didn’t wait for victory and used a network of front men to increase his chances of winning.

If successful, they had to rent out the plots to Koch Industries. The entrepreneur’s actions soon came to the attention of the public, and in 1980 the company was forced to plead guilty to five criminal charges, including conspiracy to commit fraud.

In 1979, Koch Asphalt emerged as a separate subsidiary, engaged in asphalt production and other development in this field. Later, several large factories in the U.S. and Canada were added to it. In 1987 it changed its name to Koch Materials and now owns more than a hundred plants in North America, being one of the largest subdivisions of the conglomerate.

The struggle between brothers for power over Koch Industries. Violation of environmental laws

In 1980, the struggle between the Koch brothers for power over the company itself began. Charles, taking over as head of Koch Industries, actually seized power, and his two brothers William and Frederick did not like it. David Koch was on Charles’ side, as was Jay Marshall, the fifth shareholder.

The case was being resolved in court, and after three years of arguing, Charles and David bought back the brothers’ share for $1.1 billion. The big deal was miserable a decade later, and William soon returned to the attack and sued the brothers for 18 years. Rumor has it that he even hired private investigators to investigate the company’s activities. The relationship between Charles and William has become so strained that even now the first brother calls the other one “David’s twin” in an interview, not by name.

In addition to internecine strife in the ’80s, Charles Koch was engaged in the further development of his company. In 1981, Koch Industries acquired another major plant for $265 million, this time from the Sun Company. The acquisition enabled the company to expand its gas fractionation and asphalt production activities.

In 1986, The C company was added to the conglomerate. Reiss Coal Company. This company, with more than a century of history, is engaged in the sale of coal. At that time, it had already reached 100,000 tons per year.

The company will later become part of Koch Carbon, which trades and transports minerals, cement and pulp and paper products. Construction of the Texas pipeline from Corpus Christi to San Antonio, Austin and Dallas began in 1988. It will be completed in 1990.

Speaking of acquisitions in the ’80s, it is worth mentioning the acquisition of John Zink Company, which manufactures equipment to combat pollution from the oil and petrochemical industries. The actions taken have not changed the situation, and Charles Koch has received more than one charge of environmental pollution.

In the ’80s, Kochi started another case – David became a Libertarian candidate for Vice President of the United States. Their political platform included the abandonment of social security, corporate and personal taxation and other ideas in a similar vein.

Kochi invested a lot of money in the campaign, but little success was achieved. The two main reasons for the failure were the low level of support for Libertarians among the U.S. people, at just 1%, and the extremely untimely and even partly extremist program. The failed attempt led Kochi to realize that the Libertarian Party was insignificant and switched to the larger Republican Party.

Nevertheless, Charles Koch had a significant impact on the development of the libertarian movement and even co-founded the Cato Institute.

At the end of the 1980s, another government investigation into Kohov’s activities was undertaken. This time Koch Industries was accused of stealing oil from indigenous tribes. The Indians did own fields in the United States, and Koch was their biggest buyer.

The case was investigated by FBI agents, and eventually, the Senate Committee found that Koch Industries had stolen $31 million worth of oil in three years. Koch’s lawyer turned him from an oil-stealing businessman into a victim of McCarthy and political persecution.

In addition, the entrepreneur had already changed his political stance at the time and secured the support of Senator Bob Daul from Kansas. He lobbied for the interests of an entrepreneur in Washington, proposed not to take Koch to court immediately, and expressed concern about some of the evidence on which the conclusions were based.

As a result, the commission in charge of the case, despite all efforts, failed to bring the case to trial, and the case was dismissed in 1992. The senator from Arizona was disappointed with what was happening and noted that it was one of the best cases investigated by the Senate, and it could have ended tragically for Koch, but the entrepreneur avoided any responsibility.

Charles did not get out of this case with complete impunity. After the failure of the Senate investigation, his brother William filed a lawsuit on behalf of the state, and he was able to prove that the company had stolen oil from the federal government.

The jury concluded that Koch had made about 24,000 false allegations. William filed a lawsuit for $400 million, but the jury stopped at $210 million, and Charles, using all sorts of levers, paid only $25 million.

In the early 1990s, the conglomerate continued to grow steadily. This was especially evident in the oil transportation sector – the length of the company’s pipelines reached 37,000 miles in 1994. In addition, several major acquisitions were made, including the asphalt producer Elf Asphalt and the purchase of an oil refinery from Kerr-McGee in 1995.

During the same period, the Ministry of Justice, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Coast Guard filed another lawsuit against Koch Industries. It has been accused of more than 300 individual cases of oil spills since 1990. The government has officially announced that about 55,000 barrels of oil have been spilled from Koch Industries’ pipelines.

An internal company investigation revealed that the pipelines were in such poor condition that $98 million was needed to repair them. Despite attempts to prove that some of the spills did not occur at all and to reduce the fine, Koch Industries still had to pay a large fine of $30 million.

This was not the only such violation at the time. Among them, for example, there were about 600,000 gallons of spilled jet fuel near the Mississippi River during the 1990s. According to some sources, the company turned Mississippi into its own sewerage system by discharging ammonia into wastewater.

Everything was done with intent, as it was established that the discharges were increasing at the weekend. Finally, Koch Petroleum pleaded guilty and paid $6 million and an additional $2 million to finance the rehabilitation work.

The company’s position regarding the condition of their pipelines and the ecological condition of the planet looked depressing. According to one of its former managers, no preventive or repair work was done on the pipelines as long as they remained intact. Of course, it ended in accidents.

The company management does not pay much attention to the fact that the law prescribes the prevention of possible pipeline accidents. Partly it is affected by the race for profit, in addition to the peculiarities of Koch Industries in terms of salaries and incentives for employees, the latter are forced to chase for increased efficiency, instead of stopping the transportation of oil and the prescribed prevention.

Koch’s governance is closely linked to so-called market governance. Koch Industries’ salary is, according to Charles, only an advance payment, and most employees, from workers at the conveyor to top management, are paid for increasing their own efficiency.

In the case of top management, it can be the development of a weak business direction. They will not receive a bonus for maintaining the level of profit. This approach leads to the fact that employees of all levels of preventive work on the pipeline are not profitable in terms of obtaining their own salaries. Thus, the innovative idea of conglomerate management and payment of decent compensation to deserving employees negatively affects the image of Koch Industries.

The end of the 1990s was quite successful for Koch Industries, it grew successfully, acquired companies in the areas of interest, and the Koch brothers, among other things, began to support George W. Bush’s campaign.

Among the acquired companies was the Delphi Group, which extracted, transported, bought and sold natural gas. It costed $762 million.

It also acquired Glitsch, which produces equipment for the refining, chemical, gas and pharmaceutical industries. Also worth mentioning is the purchase of animal feed manufacturer Purina Mills in 1998. A year later, this subsidiary, despite Koch’s attempts to save it, declared bankruptcy, after which it became part of Land O’Lakes. Also in the late ’90s, Koch Ventures formed its investment arm, which later became part of Koch Genesis, established in 2000.

Koch Ventures actively invested – including internet companies during the dotcom boom. Among the known investments of Koch’s company, we can mention VertiNet, which was engaged in vertical trading floors, as well as PF.Net, which is building fiber-optic networks. The latter was also invested by Lucent Technologies.

In 2000, the conglomerate established a new division, the Internet Business Strategies Group, which aimed to use Internet technologies to open new business opportunities.

Koch Industries in the 2000s. Trade with Iran

Internet investments were not the main activity of the conglomerate. In the early 2000s, Charles Koch continued to have problems with environmental laws. At the end of 2000, he was presented with a 97-point indictment – Koch Industries again broke the law and, according to the authorities, concealed the true amount of benzene emissions.

Official documents indicated a 0.61 metric tonne, which was the norm, while the actual level reached 91 metric tonnes. The company was threatened with a $350 million fine. However, in 2001, George W. Bush became president of the United States and received support from the Koch brothers in the election campaign.

Sources claim that Kochi, with the support of U.S. General Attorney John Ashcroft, reduced the fine to a symbolic $20 million.

In addition to the cases described above, there have been a number of other accidents with dire consequences for both the environment and people. As a result, Charles Koch decided to change his attitude to the issue.

One of his first actions was to conclude a deal between Koch Petroleum and the Department of Justice for Environmental Protection – he spent $80 million to make three refineries operate under the Clean Air Act.

Another important step was to abandon the huge pipeline network under the company’s control and reduce it to 4000 miles. This direction is now in perfect order, and Koch is not responsible for such a global infrastructure.

Koch Industries has also become more active in other industries, and during the 2000s several deals were made. In 2004, Invista, one of the world’s largest producers of polymer fibers, nylon, polyester, resin, and other raw materials, was acquired. It owns a number of brands, including Lycra, Stainmaster and Thermolite.

The company operates not only in the U.S., but also in a number of other countries, including the Netherlands, the UK, Germany, and Brazil. The amount of the transaction was $4.2 billion.

Koch Industries HQ

In 2005, Koch increased its conglomerate through its acquisition in the pulp and paper industry. For $13.2 billion, the company Georgia-Pacific Corporation was acquired, which was one of the leading suppliers of fabric, paper, wood, building materials and even chemicals needed in these areas.

It also owned the disposable tableware manufacturer Dixie. In addition, Koch Industries also owed a Georgia-Pacific Corporation’s $7.8 billion debt. Despite the fact that Georgia-Pacific Corporation employed about 50,000 people, its integration into the conglomerate structure was quite easy.

These acquisitions allowed Koch Industries to increase revenue to $80 billion in 2006 and become one of the two largest private companies in the United States. Purchasing and success in selected industries led some analysts to believe that it was logical for Koch Industries to enter the stock exchange soon. Charles Koch thinks otherwise, and until today he claims that Koch Industries will only become a public company over his dead body. The entrepreneur prefers to reinvest 90% of his profits in his company and does not want to depend on outside investors.

Only Koch’s acquisitions during this period were not limited to acquisitions. As early as 2000, he was believed to have been involved in lobbying for a law on the modernization of commodity futures, which has gone down in history as the Enron loophole.

In fact, it allowed companies to make unlimited speculations on energy futures and greatly reduced government regulation in this industry. To introduce this law, an Energy Group coalition was formed, which included a number of energy companies – Koch Industries, Enron, Phibro, J.Aron&Co.

During the 2008 crisis, Charles Koch’s new passion was the manipulation of oil prices. In fact, the entrepreneur took advantage of the contango situation in the futures market – the essence of which is that the futures market value is higher in the future than it is now.

Having assessed this opportunity, Koch purchased 20 million barrels of oil at a lower price and waited for an ideal opportunity to sell it by selling futures for future supply. Nine supertankers were purchased for the entire operation and filled with cheap crude oil. They were all waiting for their time in the Gulf of Mexico. On each barrel of oil, the company received about $10 from the top.

Other areas of the company’s activities during this period also elicit a mixed public reaction. For example, in 2008, it was reported that employees of Koch-Glitsch, a French subsidiary of the conglomerate, had obtained contracts for the supply of oil in six countries by paying bribes.

In an attempt to resolve this issue more quickly, the conglomerate’s management found the culprit in the person of the head of its subsidiary Leon Mausen, who was dismissed in December 2008. The French Labor Court, however, did not consider only Mausen’s dismissal guilty and claimed that he had been given full responsibility.

The consent of other managers was required for such decisions to be taken. Interestingly, Ludmila Yegorova-Farinas, who was conducting an internal investigation, was dismissed in 2009, in her opinion, precisely because of the successful disclosure of this scheme.

Another unpleasant story about Koch Industries’ activities came to light in 2011. This time, the Kochi brothers were accused of selling equipment to Iran. The relationship between Iran and the United States is hardly friendly. Moreover, U.S. companies were banned from trading with this country back in 1995. Koch Industries, however, found a loophole.

In particular, the subsidiaries of Koch Industries supplied the necessary equipment to the Iranian plant Zagros Petrochemical, which is one of the world’s largest methanol producers. Despite the public’s dissatisfaction, Koch’s lawyer claims that the entrepreneur refused to trade with Iran in 2007 when several U.S. servicemen died in the country.

Koch Industries made another purchase in 2013, with Molex, a major electronic components manufacturer, purchasing Molex for $7.2 billion, with Apple and General Electric among its customers. A year later, the conglomerate made two more purchases.

The first was the ink manufacturer and one of the leading suppliers of printing and packaging equipment, Flint Group, which was acquired from CVC Capital Partners for $3 billion. The company is located in Luxembourg and has a sales volume of €2.2 billion.

The second acquisition in 2014 was Oplink Communication, which costed $445 million to the conglomerate. The company is one of the leading manufacturers and suppliers of fiber optic components, and its customers include some of the largest telecommunications companies.

Features of conglomerate management. Political views and initiatives of the Koch brothers

The brothers Charles and David Kochi hold equal stakes in the conglomerate, with a total stake of 84%. Each of them is valued at $42.6 billion, with Charles, who is the company’s CEO and chairman of the board, doing more business. His brother is a vice president but devotes more time to political and charitable initiatives.

Charles supports the views of the critically acclaimed philosopher Friedrich von Hayek and uses the market-driven business management. Charles has achieved extraordinary success by making it seem as if he is the owner of the business he is working in. This, in turn, means that he must be able to take risks, make decisions and be ready to take responsibility.

As mentioned earlier, wages at Koch Industries are relative and there are no bonuses for employees based on the overall success of the company. Charles Koch’s will in the conglomerate puts the personal effectiveness of everyone and the growth of the areas for which they are responsible at the forefront. Stability is of little interest to Kochov – they require development. And only those who achieve this receive bonuses and bonuses.

Charles Koch maintains competition between departments and individual employees of the conglomerate. In addition, he gives even ordinary employees broad powers, and they can act without the advice of their superiors if they believe that their decision is effective.

Moreover, a talented worker who makes decisions that have an impact on growth can earn more than his or her boss. However, people who do not achieve the development of their direction and do not have high results, do not stay long in Koch Industries.

On the other hand, employees without higher education have full carte blanche who can move up the career ladder without obstacles and compete with their colleagues who graduated from university. Of course, in order to pursue a career in Koch Industries, it is not enough to be a qualified specialist, but to remain proactive, set high goals and realize them.

In order for the staff to appreciate the concept described above, Charles Koch even published his own book, The Science of Success. It explains the advantages of market management. It is now mandatory for all those who work in the conglomerate to read. Besides, as large companies are entitled to, special training is organized for the quickest adaptation of employees. The theory of market management of employees is introduced more deeply at a two-day seminar.

Charles Koch has a rather modest lifestyle and does not want to emphasize his status as one of the richest people on the planet, although his lifestyle cannot be called too ascetic. The entrepreneur is extremely demanding on his son Chase, who is now vice president of Koch Industries.

Chase wanted to play tennis professionally when he was a young man, but his father didn’t think he was doing his best. So Charles forced his son to choose between really serious tennis and work. Chase decided to work for his father and was assigned to a company ranch where he had to look after the cattle.

Managing the conglomerate is only part of the Koch brothers’ activities. A significant part of their efforts is directed at the political sphere of the United States. This is not just about lobbying for their interests, although Kochi is known for his actions in this area and the $10.6 million he spent per year.

The political views of the Koch brothers, despite their active support of the conservative Republicans, retain a libertarian outlook, with all the ensuing, such as support for the LGBT movement, as well as the abolition of government subsidies to large corporations and the withdrawal of U.S. troops from other countries.

The Koch brothers are believed to have been involved in the creation of the ultra-conservative “Tea Party”. It combines conservatism and libertarianism, and therefore actively supports Republican candidates in the elections. Koch fund the Tea Party using various structures and organizations. The entire network of organizations through which the brothers’ lobby for U.S. interests has been nicknamed “Kohtopus”.

Kochi uses their organizations to influence public opinion. For example, it is known that they resist the theory of climate change and global warming. In particular, one of the scientists of the Cato Institute challenged the arguments regarding the overwhelming problems in the media.

Charles Koch Photo

The educated movement, carrying out various actions and protests, became one of the main problems of President Barack Obama inside the country. Charles Koch tried his best to prove to Obama that the government’s active involvement in the economy could end sadly, and he sought greater freedom for entrepreneurs.

At the same time, the power of Kochs should not be overstated. For example, Obama won the 2012 presidential election despite the tens of millions of dollars his brothers invested in his opponent Mitt Romney’s campaign. However, Kochi himself claims to have “drawn conclusions from the defeat.

Kochs are famous for not denying their own mistakes. For example, they actively supported George W. Bush, and now his presidency is quite cool. Charles even expressed disappointment at his actions and failures in his book.

One of the most shocking news of the last presidential campaign was Kochi’s refusal to fund candidate Donald Trump. This is primarily due to the fact that the program of the new U.S. president diverges from the interests and ideas of his brothers.

Trump himself added fuel to the fire by refusing to meet Kohami and noting that it was better for them to talk to political puppets. Trump, an insignificant populist, published a message with this content on Twitter, after which he finally lost his brothers’ support. However, Kohi expressed dissatisfaction with all Republican candidates at the beginning of the campaign.

Time will show how the misunderstanding between him and Kohami will end for Trump. The main sponsors of the Republicans spent the “freed up” funds to support the candidates for the Senate. Even before the presidential election, Charles and David Kochi noted that they would fight to the end and leave the next generations with a greater and more successful America than they do now.